Overwork and Workaholism, Part 2: Work and Soul

This post continues the themes of overwork and workaholism from my last post. It further explores some of the soul and feeling dimensions of overwork and workaholism through music.

This post continues the themes of overwork and workaholism from my last post. It further explores some of the soul and feeling dimensions of overwork and workaholism through music.

Artistic and religious symbolism worldwhile reflects the archetype of the journey. It's one of the most universal expressions of the human condition and the development of the course of human life. The whole point of a journey is that it has a destination. This can…

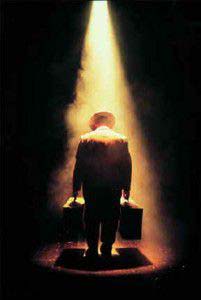

I was fortunate enough last Saturday to see Soulpepper Theatre's production of Arthur Miller's Death of a Salesman. Lots of people know the story of Willy Loman, the disintegrating salesman at the centre of the play, and the drama of his decline and eventual death.…