Counselling for Anxiety & Depth Psychotherapy, 3: Enough

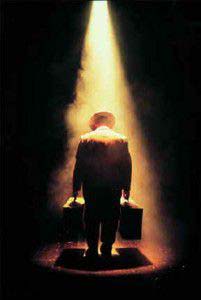

Depth case studies concerns self-acceptance, and counselling for anxiety often emphasizes that we are "enough" to deal with the situations of our lives. So, what does it mean to to feel that we are "enough"? How do we gain that level of self acceptance?