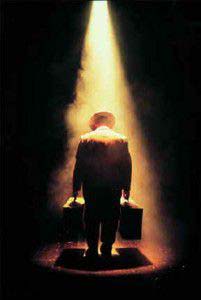

” I Feel Like I Don’t Fit in Anywhere ” : A Problem of Soul

"I feel like i don't fit in anywhere": it's the kind of thing we've all said to ourselves at various transition points in our lives. At certain key times, it can seem like a true cry from the heart.